Photographer and writer

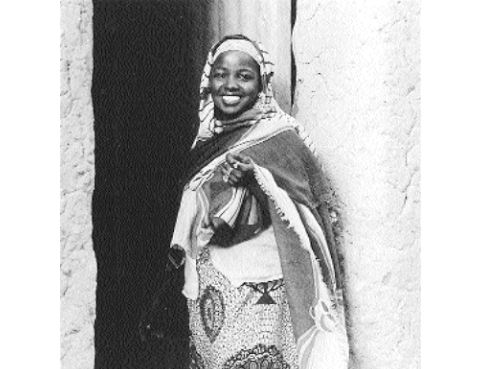

I was born in Nigeria and grew up there; I married and came over to Britain in 1982. I knew it was going to be cold, but no-one had prepared me for the winter. Because it was all dead, no leaves, I thought, ‘scientists, they’ve killed the trees’. I couldn’t understand why everyone walking around didn’t seem to care that the trees were dying. Then spring came along and I realised that everything was coming alive, being reborn. I kept saying to my friend, ‘look at those beautiful flowers’, and jumping up and down as if I’d won the lottery. At last she said, ‘you should get a camera, and stop bothering us. So I said I’d see if there were adult education classes in photography. She thought I was mad, but something had connected deep down. I enrolled in a photographic training centre in Earls Court; it was expensive and full of rich foreign students. When I finished I hadn’t decided what to do, but I went on a visit to Nigeria and took some photos when I was there. When I came back, everyone said, ‘oh, they’re beautiful!’ So that’s how it started. I gave up the business management course I was doing, because I knew I was home with the photography. I began by taking photos for newspapers, then in 1991 I began to write as well. I’d always written things down, but I’d hidden what I called my scribbles because I had an uncle in Nigeria who was a very well-known and I hadn’t wanted to compete in his arena.

Having two children of my own changed me, and the way I spend my time and what I write about. I got involved in their primary school, and though my son is in secondary school now, I’m still helping there, and it’s made me more child-oriented, more interested in children in general, not just my own.

In my Nigerian culture we have a saying that when you raise a child you must raise them to be greater than you. That has a bearing on my thinking, and the aims of my books.

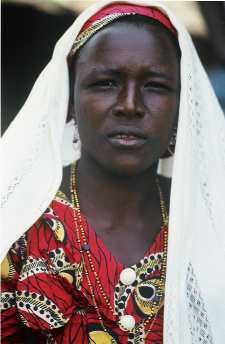

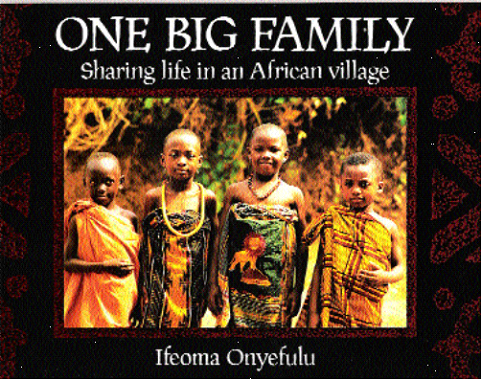

I had my first idea when I was reading to my son. The only books the library had on Africa were about safaris and giraffes and so on, and I could see how bored he was with them. Then a voice in my head started saying ‘B is for beads’ so strongly that I couldn’t read anymore. I wrote it down and rang my mum in Nigeria and asked her what it meant. She said ‘come home, think about it’. So I did, And what grew out of that was my book A is for Africa: a realistic picture of life there, illustrated with photographs. The publishers wanted me to water it down, make it more conventional and simple but I’m glad I stood my ground. Of course we have poverty and political problems in Africa but we also have weddings, births, parties, christening, people laughing. This was what I wanted to show: to balance the pictures we see on TV of war and famine. People are very resilient, they are still going about their business – whether they’re selling tomatoes or whatever, they’re trying their best. And they should be encouraged and praised. I’ve been accused of painting too good a picture; they say ‘I bet you’ve just photographed your own family, who are healthy’. But not everybody is starving; we just get on with things.

Sometimes research for my books has been difficult. I love stories about the past, superstitions and ghost stories, listening to gossip on buses. But most people don’t understand why I’m interested. They don’t like to look back. I worry that if we’re not careful, globalization will make us all become the same; I think we should value our uniqueness, our differences. Once I got a guide to take me to a remote village in northern Nigeria, because I’d heard of an interesting religious ceremony there. I should have realised that it was a mistake when I saw so many people leaving the area: soon after I started photographing, I was arrested – my guide just melted away – and I found myself being tried [for profanity?] by a Shia court that didn’t speak either my dialect or English. I felt terribly isolated, but took the advice of the lawyer they provided and pretended to be loopy; it was a relief just to be expelled from the area.

I take photos with my eyes every minute of the day. I’m always looking at people’s bone structures and thinking about how they’re put together and wishing I could photograph them; then I see them thinking, what’s she looking at, and I look away. I love listening to music – all sorts of things: African, soul, even Songs of Praise. And the smell of the forest, the leaves and the earth: it takes me back to childhood; we played outdoors a lot when I was little – smell of the forest, earthy.

I’d like to have had the family life that my parents had – my dad bringing my mum tea in the morning and my mum doing things for him; the way they joked about things. It was a warm family, where people talked and were close. There were five of us, which my father loved, as he’d been an only child. I never rebelled, although once I slammed the door when my dad was talking to me – I was 16. Everything went quiet. I came back and said ‘sorry’ then slammed it again! My parents treated me so well that I never did the things my friends did, like creeping out at night – I preferred to tell my mom.

But I didn’t have that sort of life, because my husband left in 2002. So now I’m a single mother.

My parents studied in England before they returned to Nigeria; they loved it, and that’s why they sent me over here. I still take over English breakfast tea for my father and Yardley’s lavender soap for my mother. I call England my home now, but when I go back to Africa I feel torn, and going back to England can be quite painful – as if I was two people.

I used to be afraid of death, but I’m not afraid of it now. My cousin was shot by the military when he was 32; it was a case of mistaken identity. I cried a lot and thought, what a waste, but then I had a dream about him, and he was happier in the dream, his eyes more alive, than I’d ever seen him. And I went and looked at all the pictures I’d taken of him, and I realised that in them his eyes were sad and dull – he’d suffered, had a really hard life. So I stopped worrying.

I feel most at home with people who don’t boast about what they’ve done, or want you to give an account of what you’ve done. I love listening to people telling stories, specially ghost stories.

I like to keep friends for years and years. I’ve still got friends I’ve known since I came to this country. But moving from Nigeria meant losing touch with the friends I made when I was young – when I do go back, it’s just to research a book and I don’t have time to find out where they are. So now I have more friends here than in Nigeria. I always have time for friends if they ring me up and need to talk, and I know they’d do the same for me.

I don’t feel I need much money. I’m quite careful and don’t run into debt, and I don’t spend much unless I have to buy something for my work; as to clothes I’m quite a miser, I patch things up; I don’t spend money or run into debt.

Though I don’t want more money for myself, I’d like to be able do more for promising young writers and photographers. It would be great to create a charity that would help them with both financial support and ideas , like the old system of patrons that used to exist in America and here. I know how I’ve struggled as a single parent.

What money can’t buy is peace of mind. I haven’t always had it – I did when I was young, but I lost it during my marriage break-up. But now it’s coming back. I’ve started accepting things the way they are.

Travelling has taught me that people are the same all over the world – some irritating, some helpful. When you smile, when you come with a clear conscience, people open their doors to you. We need other people. I believe that when you’re really in desperate need, someone will come along to help. Of course, if you sense someone is going to harm you, you feel on your guard, but if you feel at home you let your hair down. When I went to Oslo I found the Norwegians very welcoming – I really felt at home there. They love to talk – It made me realise why that peace agreement was signed in Oslo. I can imagine them sitting around, encouraging everyone to come up with ideas.

We all need to stop and listen to people, find out more about them, not to rush to judge them by their appearance. We should go beyond the first impression. When you do that, you find more. Maybe you met a person on a bad day for them.

Respect is a give and take thing – the way you behave to people, they will come back to that and respect you. I didn’t like listening to that American on Radio 4 saying how tough we should be on prisoners. Being locked is punishment enough. If you try to break them, you’re confirming the bad news they’ve had all their life. But you need to find out what went wrong, then there’s a chance, I bet their conscience is listening, even if they’re sitting quietly.

Someone held a door for me the other day, and at the next door, I held it open for someone else. Little kindnesses passed on like that, a smile returned, all have an effect. A little love and respect goes a long way – even if someone says they don’t want them.

Women tend to expect a lot from men and they’re always disappointed. We need to step back a bit, live and let live - though sometimes I think I did that too much! Feminism has confused men – they don’t know if they can open a door for you or not, or help you with heavy shopping in the street. But maybe that was the only way things were going to change – going straight for the jugular. But it’s had its price. You see in the newspaper now girls smoke and drink more than boys, boasting that they can outdo them. But our make-ups are very different. A woman gets drunk far more quickly than a man; we shouldn’t be drinking so much.

Women pay a price for their freedom – they have children and go out to work and still have to work when they get home; we have more work now than we had before. The balance is wrong – the man is the winner, always the winner. You might say why don’t women stay at home, but I see my children’s eyes light up when they see what I’ve done. And I’ve seen friends who have given up work and are at home and they seem to me to suffer from a complex about it.

At end of the day, it’s a matter of doing the best that you can. You may not be able to clean up all the dust in the house, but you can leave it for Saturday, or the Saturday after that. Nothing you do is a waste of time. Even if a job seems so, maybe you will learn something for the future. Even if you’re just sitting down, you’re resting.

I’ve learnt a lot about love; it’s taken me years. When you meet somebody, I used to think what mattered was whether they loved you. But now I’ve realised that’s going about it the wrong way. You have to love yourself first. If they love you too, that’s great. When you go into a relationship and you don’t love yourself, if you’re attacked, you have no defence. But if you have that self-love, he can’t hurt you. I used to think that what made you worthwhile was somebody loving you. But now I know that it’s got to come from inside you first.

I don’t mean selfishness – but if you have that peace of mind, accepted yourself warts and all – you will eventually attract people in the right way. Not many of us are comfortable in our own skin in that way. I am now. I go to the gym and enjoy it, then come back and have a shower and I feel really good. I met a friend the other day and she said, ‘look at you, you must be in love, who’s the guy?’ And I said, ‘It’s me! I’m in love with myself!’ It would be good to meet someone in the future but for now I’m OK.

I don’t want power for its own sake, or to hurt people, but if my books have the power to help people, that’s good. I don’t like analysing my work. When I’ve just done a book, I let it go; it’s like letting a child loose into the world to make its own way. I do my books for myself, what people can take from them is up to them.